A Tech Worker's Guide to Interest Rates

Over the past few years of tech industry ruin, I’ve had friends and family worriedly ask me and my wife how our jobs have been going. “I’ve been seeing news of layoffs,” they say. “Why is it that almost every single tech company seems to be tightening its belt, cutting costs, and laying people off all at once?”

Among other causes, I usually mention government interest rates. And I’m sometimes met with confusion: “What do interest rates have to do with it?”

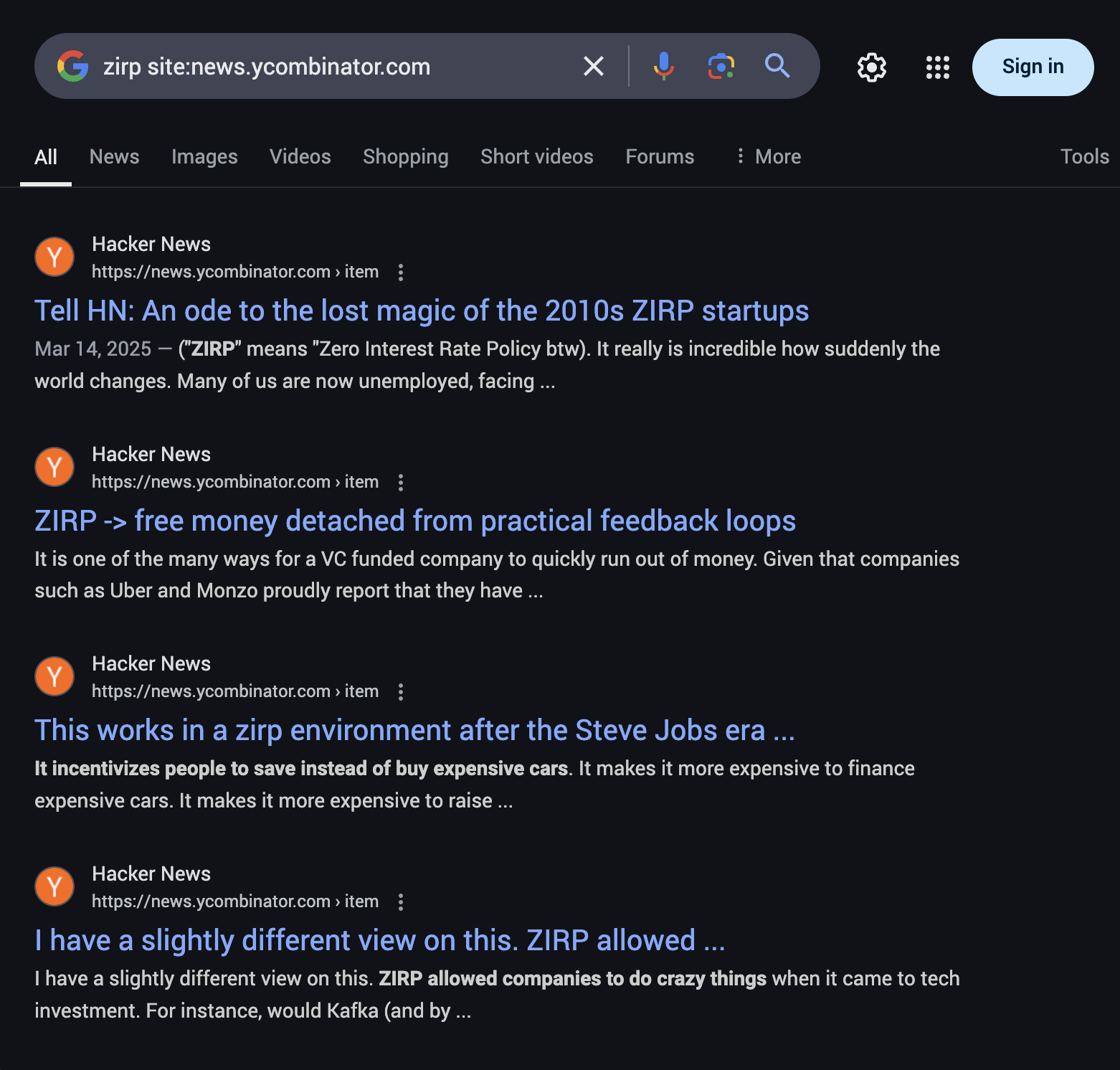

Discussions about interest rates on Hacker News, a popular online forum for techies.

Online, people also bring up interest rates. They say low rates means “money is cheap”, or that the craziness of the 2010s—where money flowed into weird startups, crypto, and NFTs—was a “ZIRP”: a Zero Interest Rate Phenomenon.1

But I find explanations of this are often aimed at people who already have some sophistication in finance and investing.

So let me give it a shot. I’ve come up with a standard answer for friends and family, and I may as well write it down.

-

Sometimes you see “ZIRP” standing in for “Zero Interest Rate Policy” instead. Same difference. ↩︎