How to Survive When the Air Itself Hates You

Around a year ago, I woke up to find that the sky was tinted orange.

As terrifying as this image looks, it was even worse in person. It was hard to capture just how orange this was, because the auto white balance in my camera kept “correcting” it.

This was around September. We’d been dealing with bad air quality on-and-off for a few weeks by then, because the CZU Lightning Complex Fires were burning in some of the nearby hills, leaving us choking whenever the wind blew the smoke our way.

But this day was different. Instead of being low-hanging smoke from nearby fires—which tended to leave the sky a hazy grey—this was high-altitude smoke from fires burning all the way up in in Oregon and Washington. As a result, the air quality was counterintuitively less bad than it had been on the worst days of the past month.

But then the ash fell.

The day that followed had the worst air quality I’d ever experienced. In the previous weeks, I’d bought myself a small air purifier and an air quality monitor. Those weren’t enough: the purifier was too small, and I wasn’t able to get the air quality in the apartment to any sort of healthy level. My girlfriend1 and I ended up having to lock ourselves in our tiny bedroom, with the door sealed off and the purifier running full blast. Even so, we didn’t do well: a ten-minute shower in the bathroom, where we couldn’t purify the air, was enough to leave me wheezing due to my asthma.

The next day, we ended up getting on a plane to Salt Lake City, in the middle of a pandemic, to escape the air. While we were there, we ordered some supplies, including another, bigger air purifier from one of the few places that still had any in stock. We stayed in a hotel there for just under a week, waiting for the purifier to be delivered, which ended up being long enough for the air in the Bay to mostly clear up.

We got lucky. If the wind had been blowing slightly more eastward, the smoke could have easily followed us to Salt Lake City.

What that experience taught me is that we were unprepared. When dealing with wildfire smoke in previous years, I’d mostly just put up with it, maybe wore a mask here or there. But those were simpler times. I wasn’t working from home, the fires tended to be smaller and the bad air quality lasted maybe a week or two at most.

2020’s fire season, in contrast, lasted over a month, with bigger impacts on air quality. And so far, 2021’s fire season is looking to be even worse. Not only that, but this isn’t just a west coast problem anymore, as the smoke is now blowing all the way across North America and even into Mexico. If anything, we’ve gotten lucky here in the SF Bay Area, with winds blowing smoke away from us, at the expense of the rest of the continent.

The Bay Area continues mainly free of wildfire smoke pollution based on the current wind pattern. Meanwhile upper air smoke from California, Oregon and Canada wildfires continues moving across the East Coast and south into Mexico (2/2) #CAwx pic.twitter.com/nNvBx0RW2g

— Rob Mayeda (@RobMayeda) July 19, 2021

With more active fires now in NW CA (#McFarlandFire among others) NW wind along the coast may bring more wildfire smoke (low to moderate AQI) our way. Smoke from Western US/Canada wildfires continues filling skies across most of the country as well. #CAwx #FireWx pic.twitter.com/efY5yDeQXO

— Rob Mayeda (@RobMayeda) August 2, 2021

After dealing with 2020’s fire season, and with the research I had done in the heat of the moment, I knew this wasn’t going to stop. From ProPublica on California’s “fire debt”:

Academics believe that between 4.4 million and 11.8 million acres burned each year in prehistoric California. Between 1982 and 1998, California’s agency land managers burned, on average, about 30,000 acres a year. Between 1999 and 2017, that number dropped to an annual 13,000 acres. […] We live with a deathly backlog. In February 2020, Nature Sustainability published this terrifying conclusion: California would need to burn 20 million acres — an area about the size of Maine — to restabilize in terms of fire.

The 2020 fires burned nearly 4.4 million acres in California. That only barely cut into California’s fire debt, and perhaps surprisingly, it’s in line with how much normally burned in prehistoric times, at least according to this article. Even assuming things improve after “catching up” with those 20 million acres, we’d still have several years of fires this big left to go. And that’s assuming that climate change doesn’t destabilize things further.

This year, I told myself wasn’t going to be caught unprepared. I’ve stocked up on filters, masks, and purifiers, I know exactly where to go to get information on air quality, and I want to share some of this knowledge with others so that you hopefully can know how to deal with this a bit better as well.

Before anything else

I’m not going to be talking about dealing with risk from the fires themselves: that’s outside my area of expertise. I’ve so far been living near fire-prone areas, not in them. I’ll be focusing on smoke.

If you do live in a fire-prone area, I can only give you the standard disaster-preparedness advice: have a plan to evacuate your area, make sure you have a “go-bag” with emergency supplies, medication, and important documents. Beyond that, I’ll direct you to the experts.

Also, as an overarching theme for dealing with smoke, or any disaster, really: the sooner you prepare, the better. If you start shopping for air purifiers, filters, and masks while you’re already choking in smoke, you’ll likely find that they’re sold out. I know this article is coming late due to the already-existing fires, but even preparing late still is better than preparing really late.

My advice is driven by my own experiences, which means it’s going to be more focused on resources for the US and the Bay Area. I’ll try to point out when things don’t apply outside these areas.

Knowing how bad things are

Most fires don’t come with scary orange skies. If you’re not very sensitive to air quality issues, you might not immediately notice that the smoke has started to roll in.

Quantifying air quality

In the US, the typical way of reporting air quality is using the Air Quality Index (AQI), a single number reported by the Environmental Protective Agency that bundles together a bunch of statistics on different pollutants. Here’s how they break it down:

| Daily AQI Color | Levels of Concern | Values of Index | Description of Air Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green | Good | 0 to 50 | Air quality is satisfactory, and air pollution poses little or no risk. |

| Yellow | Moderate | 51 to 100 | Air quality is acceptable. However, there may be a risk for some people, particularly those who are unusually sensitive to air pollution. |

| Orange | Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups | 101 to 150 | Members of sensitive groups may experience health effects. The general public is less likely to be affected. |

| Red | Unhealthy | 151 to 200 | Some members of the general public may experience health effects; members of sensitive groups may experience more serious health effects. |

| Purple | Very Unhealthy | 201 to 300 | Health alert: The risk of health effects is increased for everyone. |

| Maroon | Hazardous | 301 and higher | Health warning of emergency conditions: everyone is more likely to be affected. |

Loosely speaking, the most important component of the AQI is PM2.5, that is, a measure of how many tiny particles of 2.5 micrometers in diameter or less are present in the air, measured in micrograms per cubic meter of air. These particles can penetrate deep into the respiratory tract and even cause cardiovascular problems. Keep that in mind for later on.

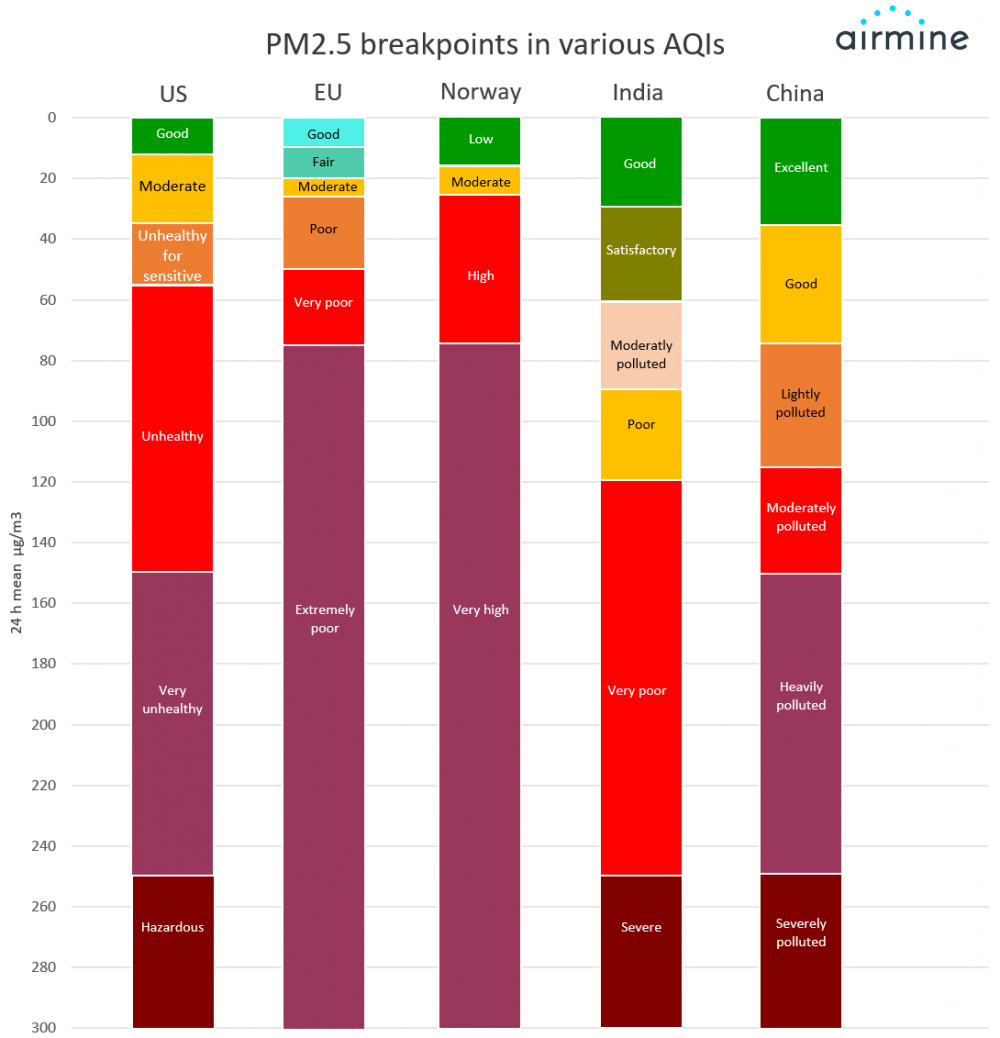

For people outside the US, one thing to note is that different countries have different definitions for their air quality divisions:

Credit for this chart goes to Marianne Amble at airmine, via /u/coopigeon on Reddit. (Updated Dec. 2022 with the original source.)

If in doubt, trust the more conservative AQI measures. You can just look at the raw PM2.5 levels and compare them to this chart.

Know how bad is it outside

The EPA’s official website for seeing the air quality index for an area is airnow.gov. Based on my experiences of last year, I don’t recommend you use the meter on their front page.

This is for a couple of reasons:

-

Their reported AQI does some kind of a rolling average over the course of a few hours.2 This is not good enough for dealing with wildfire smoke, because winds can shift far quicker than that and blow smoke into and out of your area.

-

As of last year, their AQI reading was only based on readings from a few official government sites. For example, in the Bay Area, theres’ only one in the city of San Francisco, five or so in the East Bay between Richmond and San Leandro, two in San Jose, and a single one in the entirety of the South Bay.

This is a problem. Air quality can vary significantly from one location to the next. Even 10 miles can make a major difference. If you don’t have enough sensors, you can’t tell what things are like in your specific area.

-

Just looking at the meter doesn’t give you much of a sense of how things are farther away from you. This is actually important: a larger, denser map can give you a much better picture of how smoke plumes are moving across the landscape.

Instead, my usual go-to resource is PurpleAir’s AQI map. PurpleAir is a company that sells indoor and outdoor PM2.5 monitors, and then publishes the readings from those sensors on a live map for anyone to see, using only a 10-minute average rather than the EPA’s multi-hour one. There are a few settings you need to change to make their map suitable for wood smoke, though:

-

Their sensors tend to overestimate how bad the air is when there’s wood smoke, so you’ll need to add a conversion factor on the bottom left for the best accuracy. For the US’s west coast, I recommend selecting “LRAPA”: this is a conversion factor derived from a government agency in Oregon that compared PurpleAir sensors to more accurate government sensors during the 2017 fire season.

-

You’ll also want to deselect the indoor sensors so that they don’t clutter up the map. You want to know outdoor AQI, not the AQI in random people’s homes.

If you click this link, it should already have those settings properly set for you. Zoom into your area and bookmark it, and you can use that to check the nearby air quality whenever you like.

PurpleAir’s map and sensor network became so popular in recent years that the EPA started taking their data and incorporating it into their own map at fire.airnow.gov, combining the high-accuracy government sensors with PurpleAir’s data, plus an adjustment factor. I haven’t used this site much yet, but it seems like another reasonable alternative.

Lastly, for California specifically, Rob Mayeda on Twitter is a meteorologist that talks a lot about fire and smoke, shows excellent videos of how smoke is moving (like the ones embedded above), and really helps put things into context.

One thing I’d caution you on is that it’s hard to forecast smoke. Several weather websites, as well as websites and apps like Plume Labs and IQAir, will claim to be able to forecast air quality, but in my experience they’re very unreliable. When you have nearby wildfires, the presence of smoke depends on how the wind is blowing, and the movement of air currents is chaotic and hard to predict. You can look at these forecasts if you want, but you should generally place low confidence in their predictions.

Preparing your home

Know how bad it is indoors

The typical government recommendations when it come to smoke is to stay indoors and avoid strenuous activity. Those are good recommendations, but often staying indoors isn’t enough on its own. You want to make sure that the air indoors is better than outside.

There are a bunch of things you can do to improve the air in your home and avoid letting the smoke in, but if you’re going to do any of that, you’ll need to know whether it’s working or not. This means you’ll need an indoor air quality monitor.

There are several companies that sell them. You’ll be looking specifically for an air quality monitor that measures PM2.5, and maybe CO₂ (I’ll explain why in a bit). Some models also measure volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are also bad for your health but are harder to avoid or filter out of your air.

One thing to note is that just about all home PM2.5 monitors tend to overestimate the AQI readings of wood smoke, same as the PurpleAir sensors do. So don’t freak out if they read worse air outside than the online sources mentioned above.

My personal picks are:

-

- Pros:

- This is the most well-rounded of the sensors, measuring PM2.5, VOCs, and CO₂ readings all in one device.

- It looks rather nice on a countertop or shelf, in my opinion.

- Cons:

- It doesn’t have a battery and it takes a while to start up again when unplugged, meaning it’s best kept stationary in a single room.

- Cost: $149

- Pros:

-

- Pros:

- Has a battery, which means you can unplug it and take it around several different rooms of your house to compare air quality between them.

- Cons:

- They don’t have an “all-in-one” sensor. You can get the standard Laser Egg that measures only PM2.5, the +CO2 model that measures PM2.5 and CO₂, or the +Chemical model that measures PM2.5 and VOCs, but there is no model that measures all three.

- The display, while more immediately informative than the Awair Element’s, is bright and distracting enough that I leave it off most of the time. The LCD screen also has a pretty limited viewing angle.

- Cost:

- $199 for the +CO2 or +Chemical models

- $149 for the standard model.

- Pros:

I own both of the above and have put each in a different room of my apartment.

My suggestion is that if you can only afford one, get the Kaiterra, maybe with the CO₂ sensing if you can afford the upgrade. Having only one sensor means you’d have to take it from room to room to make sure each room’s air quality is still good, and doing that with a battery-powered device is way easier than with one that needs to be plugged in.

Wirecutter has also reviewed air quality monitors (though not with a focus on wildfire smoke), so if you don’t like my recommendations you can try theirs.

Why do I recommend CO₂ sensing? That relates to my next recommendation.

Know how to seal off your home

Close your windows. Seal cracks in the doors with weatherproofing strips. If you have any fans that blow air out of your apartment, such as in the bathroom or kitchen, turn those off: you don’t want negative pressure bringing outside air in.

Beware air intakes as well. Most apartments in California have an air intake or “z-vent” that lets air in from the outside. It might look something like this on the inside of the wall:

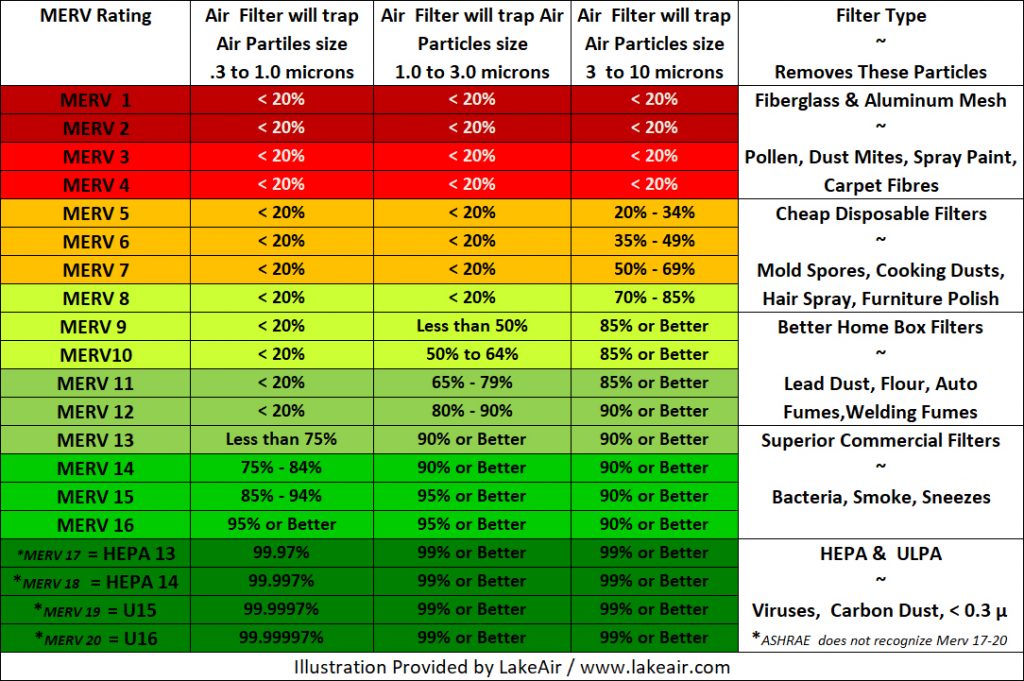

These usually have a filter in them to keep particulates from coming inside, but landlords often cheap out on the filters, don’t replace them regularly, and/or put filters in it that aren’t good enough to filter smoke. You need to make sure that:

- The filter has been replaced recently, and

- That the filter is rated MERV 13 or higher (or the equivalent ratings of MPR 1500 or FPR 10).

Only MERV 13 is really meant for capturing PM2.5 from smoke. During the 2020 fire season, my apartment only had MERV 8 filters.

Alternately, you can just seal them off entirely by taping plastic inside or over them or placing a sheet of solid material inside. Watch out for cracks.

Watch for CO₂ build-up

The problem with sealing off your home is that you lose out on fresh, oxygen-rich air. You’re constantly breathing in oxygen and exhaling CO₂, and a completely sealed home can often cause CO₂ levels to get uncomfortably high.

CO₂ won’t kill you, nor will it really have severe health effects, unless the concentrations get extremely high. But it may make you feel sluggish, sleepy, and make it hard to think. If you’re still working from home, this could be a problem.

This is why I suggest to get an air quality monitor that measures CO₂. You’d be surprised at how quickly CO₂ levels can build up in a small room or apartment from nothing but breathing, especially if you’re doing any sort of exercise or physical activity.

I’d suggest striking a balancing act: when the winds shift and the air outside improves a bit, open the windows and let some fresh air in, then close them before it gets too smoky. This is why you need to know the real-time air quality outside, and why PurpleAir’s frequently-updated map is really important.

But this does likely mean you’ll be letting in a little smoke. And it’s likely you won’t be able to completely seal off every crack in your home. So how can you get rid of smoke once it’s already inside?

Buy an air purifier

This is the most important recommendation of the bunch. I’d still recommend having an air quality monitor, so that you know whether or not the purifier is working well enough, but an air purifier is really the only way you can get rid of smoke once it’s already inside your home.

At this point, I don’t have any recommendations for you that are better than what this Wirecutter review already says. They put several different kind of purifiers to the test in real-world scenarios, and their recommendations seem pretty solid. They even tested the cheapo option of duct-taping a box fan to a furnace filter.

The one warning I’d give you, though, is pay attention to the size of the room they’re recommended for. Err on the side of buying a bigger purifier, and/or buying more than one (maybe one for each room you’ll be occupying).

In the early days of the 2020 fire season, I ordered Wirecutter’s first recommendation, the Coway AP-1512HH Mighty. It worked okay when the smoke was mild. But when the smoke got really bad, it wasn’t strong enough to keep the air in my whole one-bedroom apartment clean, even when running at full blast. It worked fine for a small room the size of our bedroom if I kept the door closed, but if I opened the door it was completely incapable of keeping the rest of my apartment clean. We ended up having to scramble to buy any bigger purifier we could get our hands on at the peak of the fire season, when they were sold out almost everywhere.

Prepare yourself

You might not be stuck at home during the fire season the way I was in 2020. There are still things you can do (or not do) to help protect yourself even if you’re not at home.

Buy yourself N95 respirators

Yes, they were in short supply at the beginning of the pandemic, but there’s plenty of supply now.

Filtering smoke and particulate matter is exactly what N95 respirators were made for, so take advantage of that. Make sure that they make a good seal around your face. You should be breathing through the fabric of the respirator, not around it.

If you have trouble keeping your home’s air in a good state, you can also use these indoors for extra protection.

Stay indoors as much as possible

In almost all cases, the air indoors is going to be better than outdoors. If you’re in a building with an HVAC system, they’re going to have some filters in the air vents which should remove some of the particulates from the air.

Avoid strenuous exercise

I mentioned this above, but the more exercise you do, the more you have to breathe. And the more you breathe, the more smoke you’ll inhale. Let yourself be a bit more sedentary until things get better.

If you need respiratory medication, have it ready

If, like me, you have asthma, make sure you have some unexpired inhalers ready.3 Same goes for any other medication you might need. You don’t want to be scrambling to call a doctor for more.

You can, in fact, do this

I know I started off this article by making this all sound pretty scary, but the reason I wrote this is because this is manageable. These are all practical things that you can do to help ride out the smoke.

Every fire goes out eventually, unless you’re in the Sun or in Turkmenistan.4 Even if it takes a while for the fires to go out, it’s not uncommon for the wind to shift and give you a (literal) breather.

In the meantime, you can keep your home clean, keep yourself protected with a respirator for when you do need to leave, and keep yourself informed as to how things are progressing.

Eventually, the sky will turn blue again.

-

Now my wife. ↩︎

-

See page 7 of this document for details. ↩︎

-

My asthma is pretty mild, and so it’s not uncommon for me to find my inhaler has expired when I do end up needing it because of a cold or smoke or something. ↩︎

-

And even those will go out eventually, for a much longer definition of “eventually”. ↩︎