Scenes from Silicon Valley

It’s been just over two years since I first moved to Silicon Valley.

Ever since I wrote Scenes from New York, I always intended to put together another collection of photos for the San Francisco Bay Area. But two years is a long time. For Scenes from New York, I had only been living there for nine months. The city was still new to me, and I could still comment on it as if I were an outsider.

But here, now, in California? I’ve gotten used to its quirks, its advantages, and its dysfunctions. That makes it harder to talk about this place objectively in a way that people from the outside would understand.

But still, I’m going to try anyway.

If you ask a local where Silicon Valley is, they’re actually likely to exclude San Francisco from that definition. Strictly speaking, Silicon Valley is the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, stretching from around Redwood City to around San Jose.

But I’m writing this for outsiders, not for locals, so I’ll use the more inclusive definition. Besides, San Francisco makes for pretty pictures.

This is the view from Coit Tower in San Francisco. From the look of this view, you’d think this was an especially tall tower. It isn’t. Instead, it’s the land it’s built on—Telegraph Hill—that makes it stand tall even compared to the skyscrapers in the distance.

In fact, tall buildings in general are pretty scarce in the Bay Area, and a lot of long-time residents really don’t like them. But even when the buildings don’t vary in height as much, the ground itself tends to make up for it.

Even though I’ve lived in cities all my life, I didn’t actually end up living in San Francisco proper. It’s hard to live in the city when your job is too far south. Commute times start exploding, and traffic is awful.

Part of the reason for both of those things is because the majority of the Bay Area actually looks more like this picture: endless suburban homes, sometimes not even two stories tall, connected by roads and highways. It can actually be kind of stifling if you live there, particularly if, like me, you don’t drive. There are long stretches of land where there is literally nothing within walking distance but individual homes, offices, and highways.

San Francisco was too far. I knew I wouldn’t be able to live there. But when I had my internship here, I was placed in housing near Sunnyvale, that was just off a six-lane major street, surrounded by parking lots, and a forty-five minute walk from the nearest train station.

It was fine for three months, but I promised myself that if I came back to live long-term, I wouldn’t stay in a place like that again. I needed a compromise.

For me, Redwood City was that compromise. It’s one of the few places in the South Bay that’s actually been building and zoning for density, with homes, restaurants, grocery stores, a movie theatre, and a train that can take you all the way down the Bay in both directions, all within walking distance.

It’s also one of the few places that’s actually building housing around here. If you’ve heard about the San Francisco housing crisis, you should know that it’s absolutely real, and it affects every single person that lives here. Redwood City is a small exception to the obstinacy you get against building apartments and larger buildings, and I think it’s been for the better.

And of course, sometimes they have cool events downtown, like this light show they run on Tuesday nights during the summer.

If you think I’m joking about the housing crisis, I’m not. One-bedroom apartments are easily $3000 to $3500, two-bedrooms $4500. Modest houses are in the $1 million to $2 million range. Even the ads know this.

Ads here do more than just joke about housing costs. In fact, this place has some of the most hyper-specific ads and billboards I’ve ever seen. You see ads about products for tech startups, investing in tech startups, hiring for tech startups, ice cream companies pretending to be tech startups… and ads that are clearly orienting themselves towards the local weed-friendly and “woke” culture.

This feels like a symptom of the Bay Area’s monoculture. In New York, if you met a person with money, that person could be a banker, a performer, a fashion designer, or any number of other careers. Here, most people with a lot of disposable income are either in tech or tech-adjacent jobs, and the ads reflect that reality.

Thankfully, in contrast to New York, the ads haven’t yet taken over the skies. Instead you get this. I think I like this better.

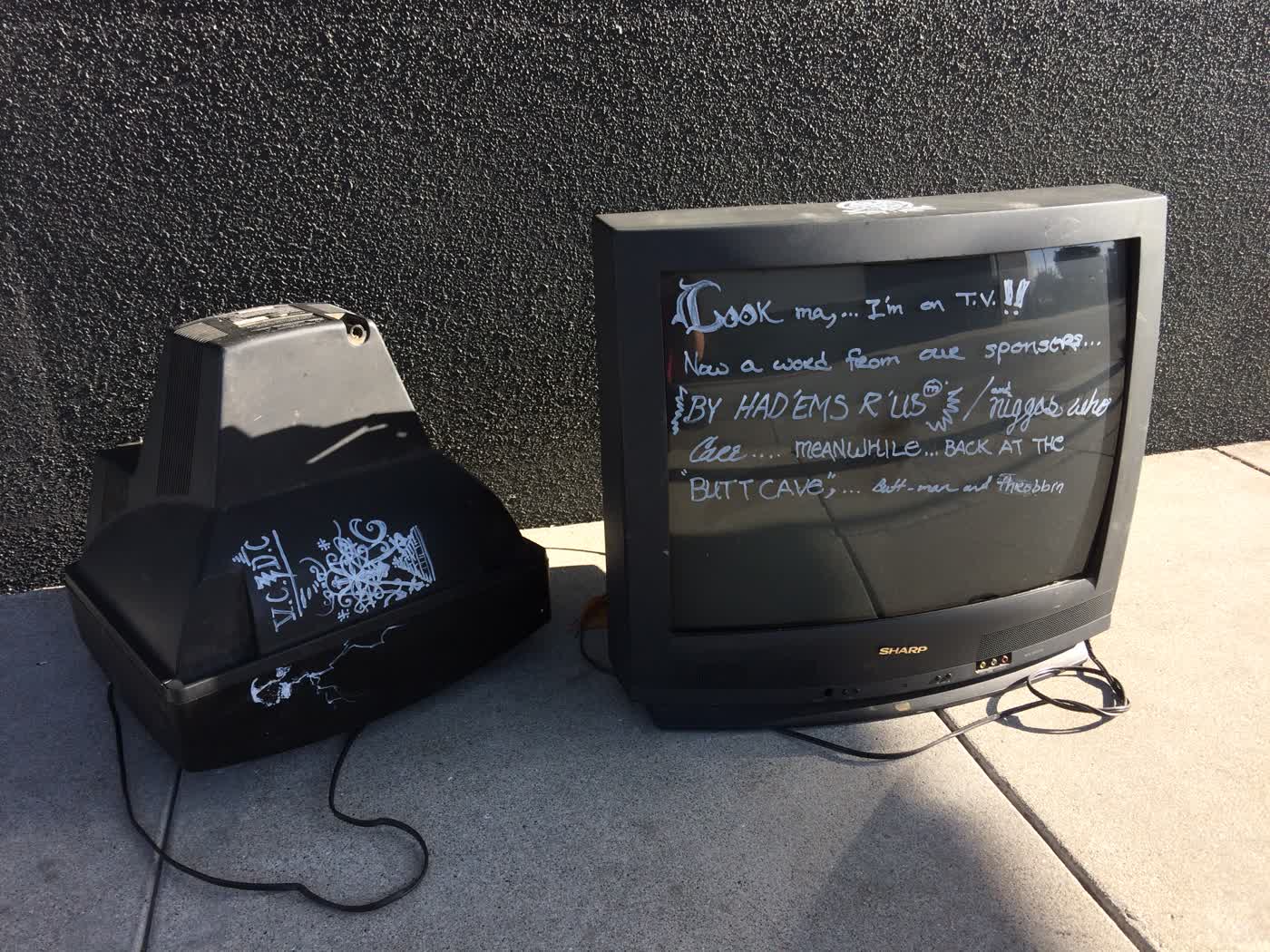

Sometimes you just find something that kind of defies commentary.

You see a lot of blue skies here, that’s for sure, and people take advantage of it, like here, in Dolores Park. In the summer, you get months on end without rain, and whenever it’s hot, it’s a dry heat that means escaping it is as simple as getting into the shade.

It actually reminds me a lot of the weather in Portugal. With most of my heritage coming from there, I swear I feel like I’m more well-suited to this kind of climate on a biological level.

If you have the kind of climate that can grow palm trees, and you’re in the kind of culture that celebrates Christmas, I feel like things like this will happen pretty naturally.

The other thing that happens naturally in this dry kind of climate, though, is fire. We’ve had two major wildfires in the past two years, the Napa fire of 2017 and the Paradise/Camp fire of 2018. Neither of them were close enough to actually threaten my home or work, but both of them were close enough to cause our air quality to plummet. People were advised to stay indoors in places with air filtration, and in the case of the Paradise fire in particular, the air quality was actually rated as not just unhealthy, but hazardous. This dust mask and my asthma puffer were my lifeline.

On the plus side, the sunny weather here means that biking is a viable method of commuting. I was never much for biking in places like Toronto or New York, because in the winter months biking becomes risky and unpleasant as you make your way through snowy, car-filled streets. But here, a bike can often be a good, viable alternative to a car for moderate distances.

If you’re willing to go a bit farther, you can even take your bike to some interesting natural places. Just be careful of the hills, especially if you’re out of shape. I damn near died taking my bike up here.

Transportation can be an issue here though. For short distances, taking a bike is fine. For longer distances, either you take a car and deal with the traffic, or you take the train.

For me, the train is my lifeline to the rest of the Bay Area, and an important one at that, since I’m in love with a wonderful girl who lives in San Francisco. But on evenings and weekends, the train only runs once every hour to hour and a half, meaning that while I’m in the city I’m keeping a close eye on the clock. Missing the train means having to either wait another hour and a half, or paying a pretty penny for an Uber back home.

Because public transportation is poor, the housing is low-density, and the region is built for cars, the bigger tech companies do what they can to compensate. They know that neither the roads near their offices nor their company parking lots can handle every single one of their employees commuting to work in their own individual cars. Instead, they encourage alternative means of commuting such as carpooling and biking, and they provide private buses for places where public transportation routes to their offices don’t exist.

Sometimes you may read articles critical of these buses, saying they’re “luxurious” or even “rolling gated communities”, implying that the only reason they exist is to flaunt these companies’ wealth. Don’t buy into that hype. These buses are a band-aid solution to the lack of non-car-based transportation in the Bay Area, especially to the highway-adjacent offices of tech companies. Their existence keeps hundreds of cars off already-congested roads, while the Bay Area gets its act together around public transportation.

Because of this place’s reliance on cars for transportation, it makes sense that this would be the birthplace of more car-focused transportation start-ups. Uber and Lyft never made sense to me when I lived in New York. But the moment I started living here, it clicked: when going into the city, even though I was taking the train, I often had to Uber to the train station, ride the train all the way to San Francsico, and then Uber from the train station to my destination in the city.

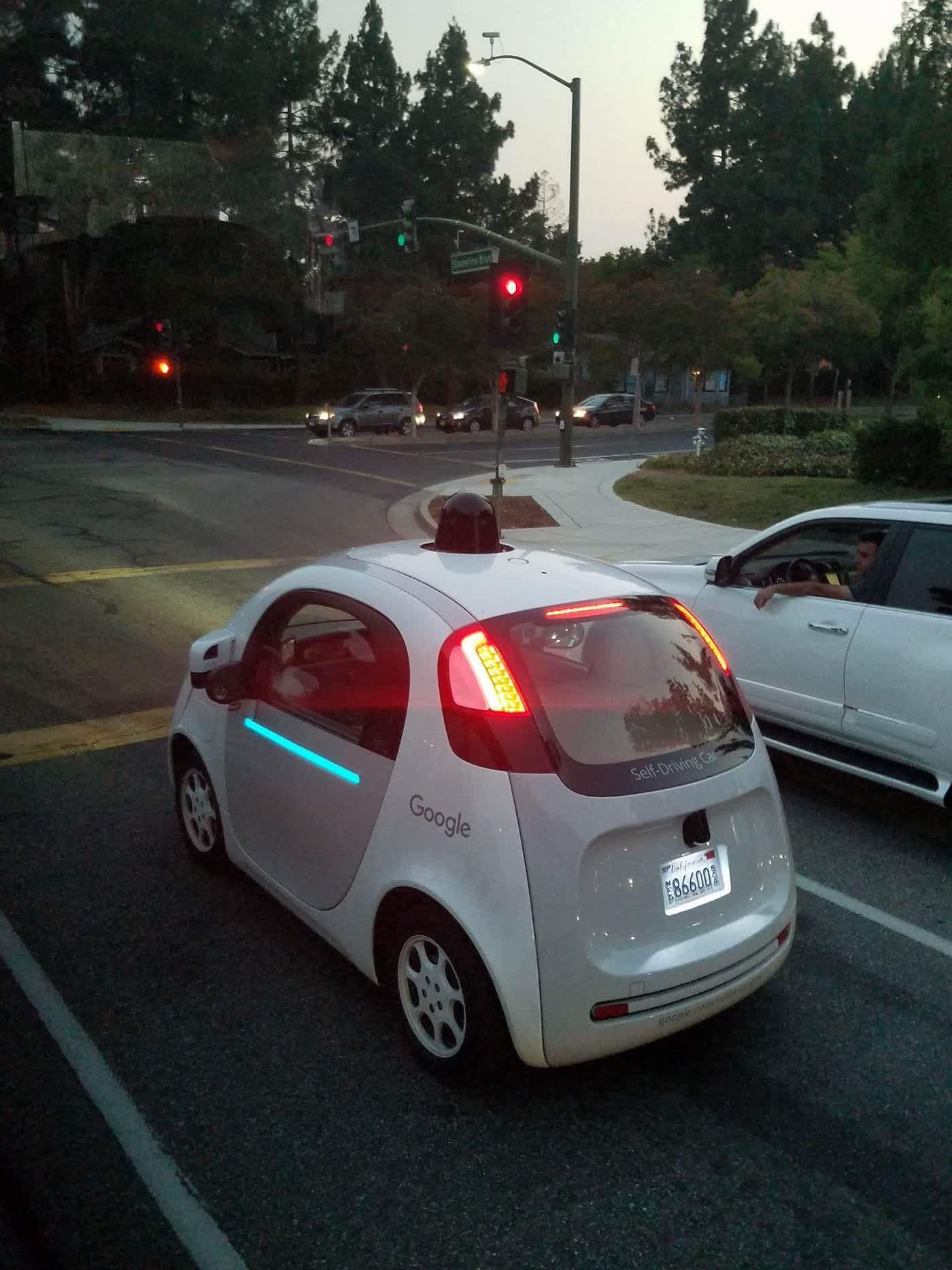

Living here made Uber make sense, but it also made self-driving cars make sense. You might think those are strictly in the future. Practically speaking, yes: you can’t actively hail one. But if you happen to be around the Mountain View area, it’s not uncommon to see one of these little guys zipping around, with a human driver in the driver’s seat acting as the AI’s “driving instructor”.

Every once in a while, particularly when I first moved here, I’d experience what I came to call a “Silicon Valley Moment”. It’s when you’re riding in a company shuttle and look outside the window to see a self-driving car, or when you pass by a UPS store and see a “We 3D Print!” sign in their window, or when you’re walking around downtown Redwood City to see these tiny little robots zipping around. I haven’t seen them in the past year or so, but around 2017 they seemed to be around pretty frequently. Rumour has it that they were from a startup trying to do robot-based food delivery.

One of the weirdest Silicon Valley Moments I ever had was one time during my internship, in downtown Palo Alto. I was walking down the street with a few friends, when I heard a cheery “Hello!” from a nearby storefront. I turned to see what looked like an iPad on a stick with wheels greet me from the store’s doorway as I walked by.

I found out later out it was a store selling telepresence robots, that was completely staffed by telepresence robots. That store doesn’t exist anymore, but that memory is going to live on in my mind as the most “Silicon Valley” thing that has ever happened to me.

Another crazy thing that happened around the time of my internship: Pokémon Go launched. And especially here, of all places, it was a phenomenon the likes of which I’ve never seen since. The stories—of people randomly congregating at Poké Stops, all with their phones out, chatting and playing the game—were absolutely true.

I even got in on the action a bit myself, until near the end of my internship. But after a month or two, I started realizing that it had been infiltrating a lot of my quiet, personal time and replacing it with the distraction of constantly checking my phone. I was frequently looking for Poké Stops and interesting Pokémon in the vicinity.

I uninstalled the game shortly after. I was already feeling starved for quiet, contemplative time in the rushed culture of the Silicon Valley technology industry, and the game just made it worse.

Facebook’s campus in Menlo Park isn’t the most tourist-friendly place. Unless you know someone that works there, you’re not getting in, and the only thing that you’ll be able to see are the boring outsides of the buildings, the nearby highways and parking lots, and the Like sign just outside their main campus.

And yet, apparently some tourists still stop by there on occasion, just to take a picture near the Like sign and leave. I can’t say why. But if you find yourself there, I’ll tell you that sign actually holds a bit of a secret: go around the back side of it, and you’ll see the old Sun Microsystems logo, from the company that used to own that campus before Facebook moved in.

Legend has it that Facebook kept that there deliberately, as a sobering reminder to their employees about what happens to tech companies that don’t move fast enough to survive.

Everyone who visits has to have at least one picture of the Golden Gate Bridge. In keeping with my tradition from the last article of taking an unorthodox picture of the area’s most famous landmark, this is my favourite. To me, this feels like it symbolizes some of the issues the area has had in coping with such drastic changes over the past few decades.

And much like in the picture of the Statue of Liberty in the last article, I’m part of that problem, part of those changes.

I can often feel that hostility myself. The influx of tech workers are blamed for the increase in cost of living (arguably true, but only because it’s been paired with a critical undersupply of new housing to accommodate them) and for the change in the character and culture of local neighbourhoods (also arguably true, but for which I can offer no excuse).

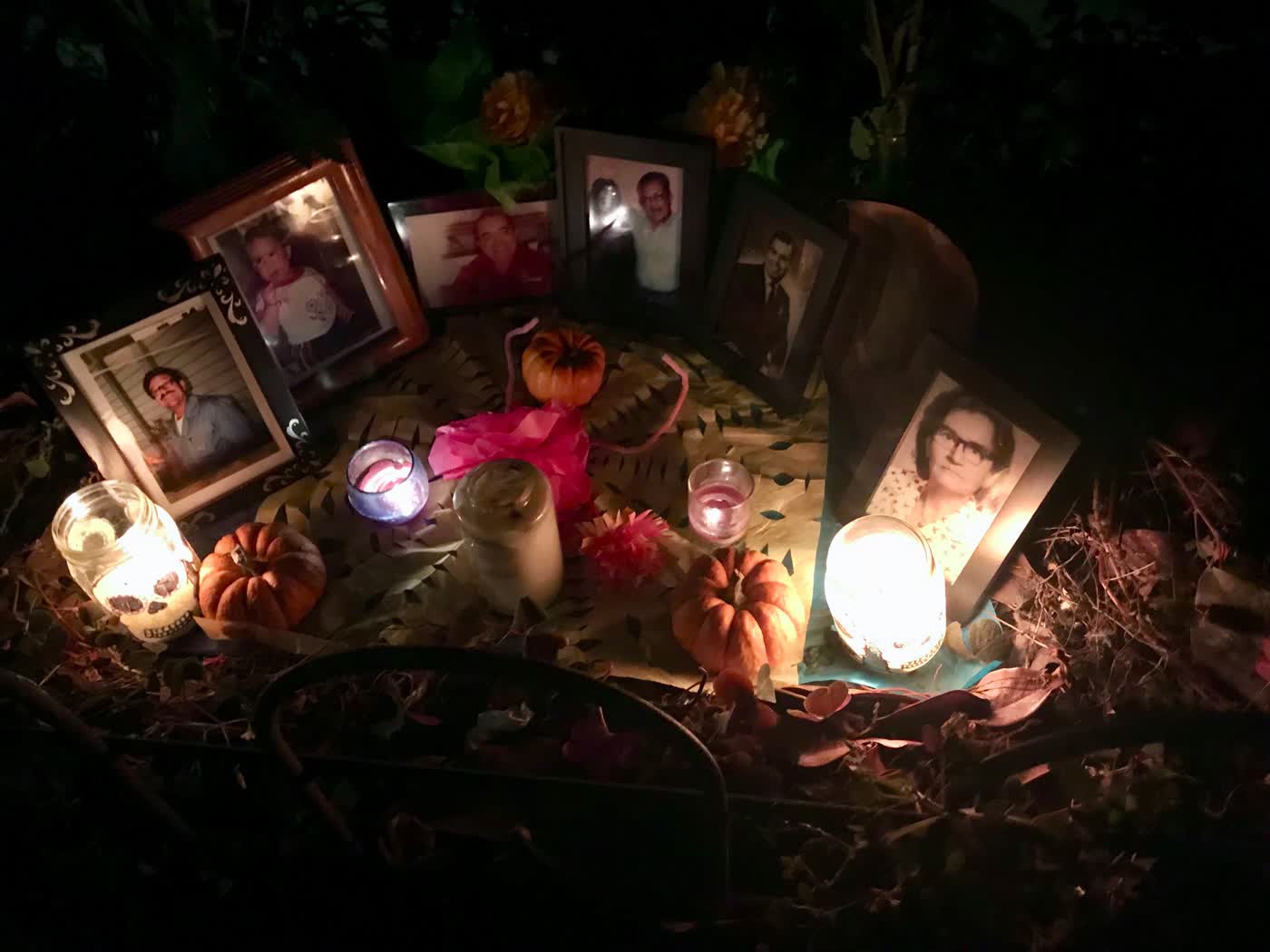

Honestly, a lot of the neighbourhoods do have an interesting character to them. This, for instance, is an ofrenda, an offering to the dead, that was placed on the porch of a home in the Mission (one of the traditionally Hispanic neighbourhoods of San Francisco) during the annual Día de los Muertos parade.

But even in the parades and festivals like Día de los Muertos, you still can’t escape the local politics. That undercurrent of resentfulness is still there.

A lot of the local hostility towards tech comes down to income inequality combined with high cost of living. And that inequality can be striking. This picture is of the United Nations Plaza, an ostentatious open space that looks out on the San Francisco City Hall in the distance. It’s just a few blocks from multiple major theatre venues, an art museum, and a concert hall.

It’s also right next to the Tenderloin, a neighbourhood of San Francisco that is the homelessness capital of the United States. One of the aforementioned theatres is even inside the Tenderloin.

I once went to a musical at that theatre as a part of a company outing during my internship. I’ll never forget the sight of seeing a bus full of young, rich tech interns lining up for a musical they weren’t even paying for, right next to a half-dozen homeless people in sleeping bags.

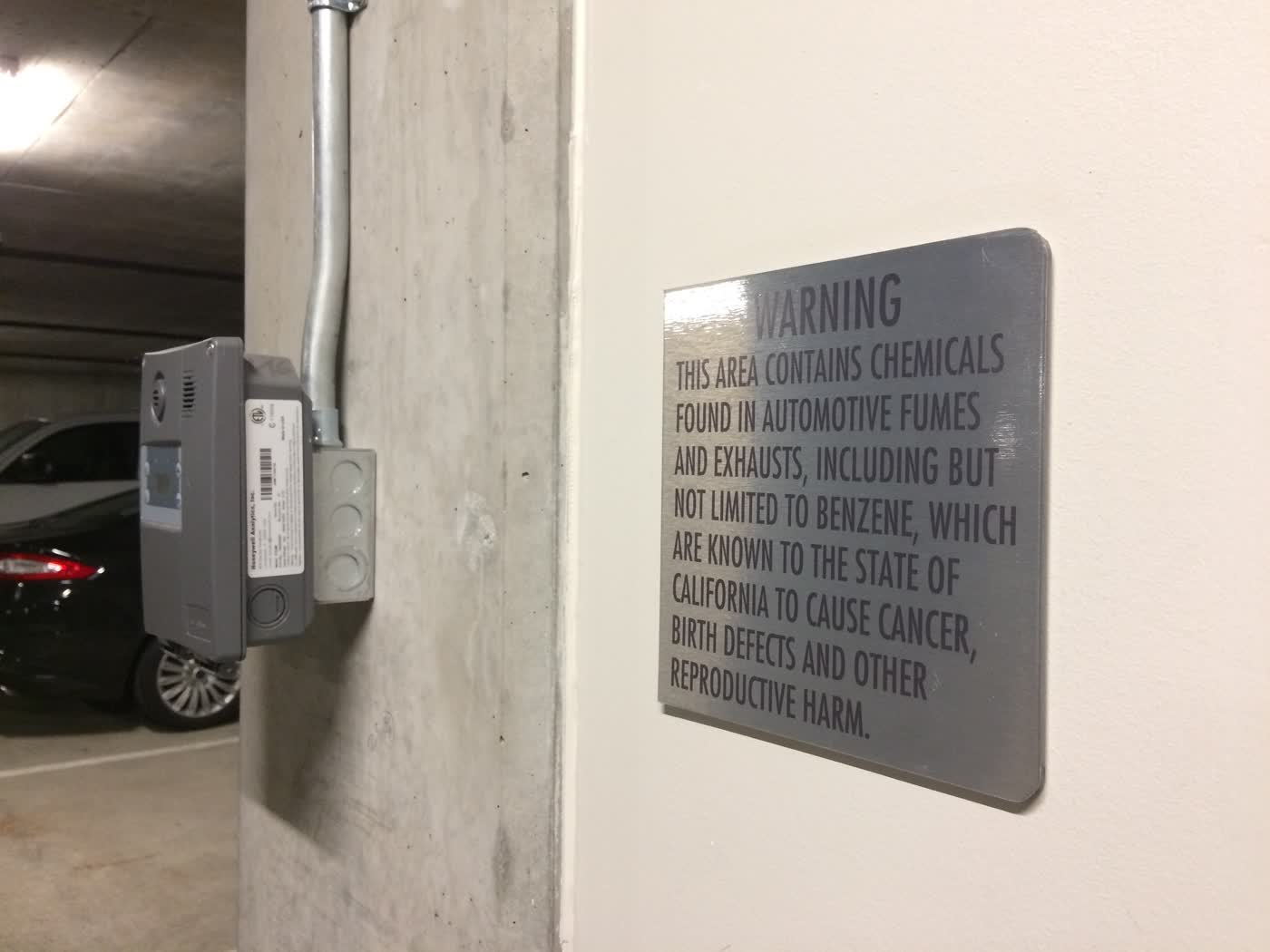

Spend any amount of time in California, and you’re likely to see many permutations of this sign in a huge number of places ranging from parking lots to sushi restaurants to Disneyland. These signs exist because of a well-intentioned law gone awry.

The intent behind the law, which was placed on the ballot in 1986 and was passed by popular vote, was to ensure that businesses can’t quietly expose people to chemicals that cause cancer or birth defects (from a list that the California government maintains). If a private citizen finds that a business is exposing their customers to any of these chemicals via the business’s facilities or products, the citizen can sue. The only way businesses can avoid lawsuits is if they either run a study to prove that the level of chemical exposure is low enough to not have health consequences, or to put up a sign or label saying that you might be exposed to these chemicals.

Business owners usually look at the cost of running a study, compare it to the cost of putting up a sign, and choose the sign. People here see these signs so often that they’ve become used to it, so it’s rarely a hit to their business. And so the signs proliferate.

Ever since I wrote the article Sakura back in 2012, I’ve made it a point to go out to see the cherry blossoms every single time they’re in bloom.

I’ve managed to keep this tradition up everywhere I’ve lived since then, since I’ve always managed to find a park with cherry blossoms. In Toronto it was High Park, in New York it was the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, and here it’s the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco.

It’s become something of a personal ritual every year, a way to keep me grounded and help me reflect.

I’ll leave you with one last look at the California sun over the mountains.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading.

Forgot password?

Close message

Subscribe to this blog post's comments through...

Subscribe via email

SubscribeComments

Post a new comment

Comment as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.

Comments by IntenseDebate

Reply as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.