The Dark Side of Fame

Back in 2010, when I was still in the midst of university, I was at a friend’s house doing some work for the University of Toronto Game Design and Development Club. I was the Vice President of the club that year, and as a member of a completely new team of executives, we had our work cut out for us in handling the responsibilities that our club demanded of us.

So we worked through the afternoon, discussing ideas and directions and plans and requirements. And then the evening hit, and we were done.

And then, my friend turns to me and asks me to try out this cool little game called Minecraft.

It was an odd little specimen of a game. It was a game that was completely free-form, with no explicit goals. The world was made of one-cubic-meter blocks, all textured with pixel art, and the world was infinitely modifiable. It was still in Alpha, which meant that it was under heavy development and was still quite buggy and incomplete. But it was being sold for money, at a discount for those who bought it in those early stages.

Except, that is, for that weekend. Turns out the game had been getting so popular that it had broken the servers its website was hosted on. So the game’s sole creator, a guy known as Markus Persson to his friends and family and as Notch to people on the internet, had declared this a “free weekend”, allowing people to download the game for free while he fixed up the servers that would allow people to actually pay for the game.

We set up a local server on my laptop, he fired up the game on his desktop, and along with his roommates we played for hours on a shared world, to the point where I had to force myself to shut it off and go back home before the subway service closed for the night. I built a sandcastle with a face. My friend delved into the earth to mine a mineral that could be used to make logic gates and computers. And we had fun.

Yes, that’s the page with the subway’s closing hours in the background.

The game was still very unfinished then, especially the multiplayer mode that we were playing. There were no monsters, you couldn’t take damage, and the networking would occasionally bug out and make blocks you placed down disappear.

But despite that, I could see that this was a game with a massive amount of potential. It was fun, it was like nothing I’d ever played before, and I was hooked.

And so were millions of others.

Let’s take a break and look at another story.

Back in 2013, one of the bigger triple-A titles out on the market was Call of Duty: Black Ops 2. Another entry in the long-standing Call of Duty series of military shooters, this was one of the biggest releases of the year and was a game that sold millions during its first year of release.

It had been released in the holiday season of 2012, and since that date it had created a pretty substantial community of online players. But as tends to happen with competitive online games, balance issues with the gameplay mechanics had become more and more apparent as more and more online games were played. And so it was that in July 2013, CoD:BlOps2 got an update to tweak the game balance. An update that reduced the damage and rate of fire of a few of the guns in the game.

Some people were really unhappy about this. Some people were really, really unhappy about this. There were a lot of people who, evidently, really liked those guns, and the discovery that they had suddenly become less powerful interfered with the power fantasies that these people had been building up within this game and its online community.

And so they got angry, and they went to Twitter to vent their frustrations. And the person who got the brunt of this was David Vonderhaar, the studio design director for Treyarch, the developers of the game.

David Vonderhaar.

He got everything from demands to revert the changes, to insults about his baldness, to people wishing death and disease on him, to threats of violence to him and his wife and daughter, largely through Twitter. Dozens, if not hundreds of angry messages from people who were upset that his team had changed the fire time of the DSR 50 sniper rifle from 0.2 seconds to 0.4 seconds.

These threats were mainly empty ones—the kind of people who make them are not typically the kind of people who stay tough once they’re out from behind their computer screen—but he still had to deal with a massive torrent of negativity that lasted for days if not weeks. For someone who interacts with their community frequently, as many game developers do these days, that can be difficult to deal with. And deal with it he did, until eventually it all blew over.

Minecraft quickly turned into the most important game of the decade. Its popularity kept increasing, spurred on mainly by word-of-mouth as well as word-of-mouth-by-proxy, through things such as player-created Youtube videos. Minecraft did no traditional marketing. No ads, no billboards, nothing of the sort other than a few short videos uploaded by Notch to Youtube, showing off new features he had developed, and a bare-bones website. Its success was entirely grassroots.

Not only did it become popular, but it challenged the way some people saw game development. It popularized the idea of selling a game during development. The current phenomenon of “Early Access” games had its genesis with Minecraft. It led to a resurgence in games with procedural, randomly-generated content. It spurred more people to develop games about building and survival, inspiring games such as Rust, Don’t Starve, and Terraria. And, since it had been developed primarily by one man, it upended the idea that the best games came out of the bigger studios, the idea that the games that were most fun to play were the ones that had massive resources backing them, inspiring independent game developers around the world to try to achieve the same success that Notch did.

My character in the game, dyed in U of T Engineering purple, in a desert greenhouse I built.

Notch, on his part, kept on developing the game. He used the money coming in during the Alpha stage of the game to set up his own company, Mojang AB. He hired a team of developers, including former friends and co-workers of his, as well as people from the Minecraft modding community. And the team kept communicating openly with the community for the sake of guiding development.

But he never seemed very comfortable with his success. He maintained a humble attitude in dealing with his fans, and always seemed a bit overwhelmed by his sudden celebrity status. Although he was the majority shareholder of Mojang AB, he did not take the position of CEO, preferring to keep his development job so he could still be close to the game.

The game kept growing in popularity regardless.

Let’s take another break.

I’ve had a few friends who have struggled with issues of mental illness and depression. I’ve always tried my best to help where I can, but as is common with friends of those struggling, there were times I had trouble really understanding what kinds of things they were dealing with and what kind of help was actually constructive.

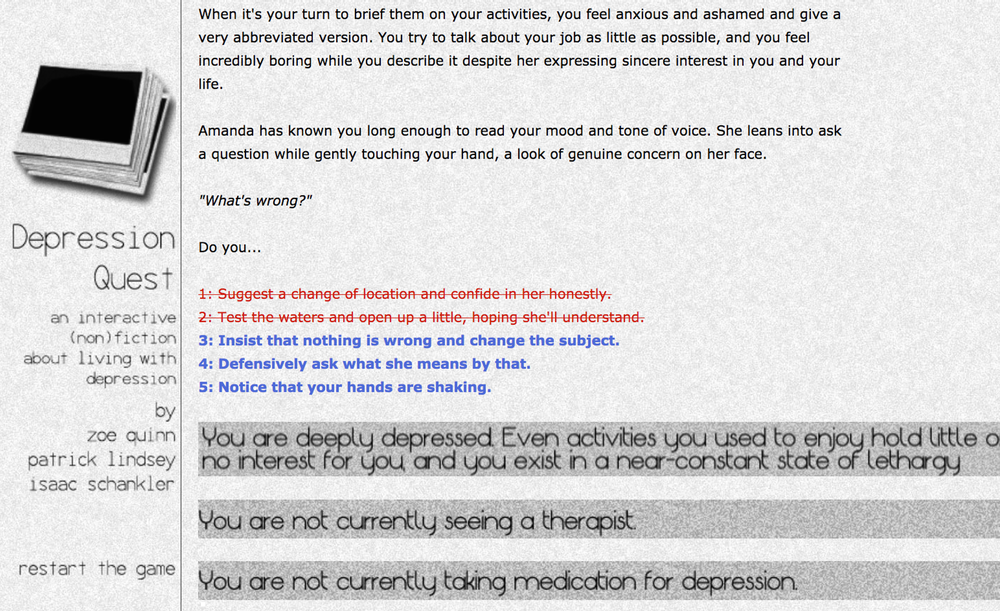

Somewhere in the middle of all this I started becoming more sensitive to issues relating to depression, and started looking into resources where I could learn more about it. And among the things I came across was a game called Depression Quest.

Created by a solo developer by the name of Zoë Quinn, the game is a simple, text-based affair, but it’s one that cuts straight to the heart of what makes depression so difficult to deal with. It’s free to play, but takes donations, with a portion of the donations going to charities that deal with depression and suicide.

It’s a difficult and very emotionally charged issue to breach, and games are an unconventional medium through which to approach it. Combined with the fact that many people experience depression differently, this means that the game doesn’t necessarily speak to everyone. As with Notch and David, however, Zoë tends to be very open with her fans and active in social media, and the combination of these things meant she opened herself up to a lot of hatred for her game.

This all came to a head last month, when an ex-boyfriend of Zoë’s posted a long, angry series of blog posts detailing how Zoë had cheated on him multiple times during their relationship. Rather than dealing with this matter privately, he posted the details publicly on the internet, causing a massive outpouring of hatred. And among the men named in as affairs were prominent online game journalists which had written about Zoë or Depression Quest, prompting the angry commenters to frame the situation as, “Zoë Quinn had sex with journalists for coverage or positive reviews”.

Thus began an angry and complex mess that still has not been resolved or fizzled out. Zoë’s blog was hacked, with her personal information—including her home address and phone number—posted publicly. She has been subject to more abuse than ever before, including threats of violence and death. She’s since been staying at friends’ houses, keeping herself safe, presumably waiting until the internet hate machine gets tired of her.

At the end of 2011, the “final” version of Minecraft was released. In this case, the word “final” didn’t mean much, as development had been ongoing both up to that point and afterwards, with frequent content updates to the game that continue to this day. But shortly after this “final” release, Notch stepped down from Minecraft development, letting his team, led by Jens Bergenstein, take over full-time development.

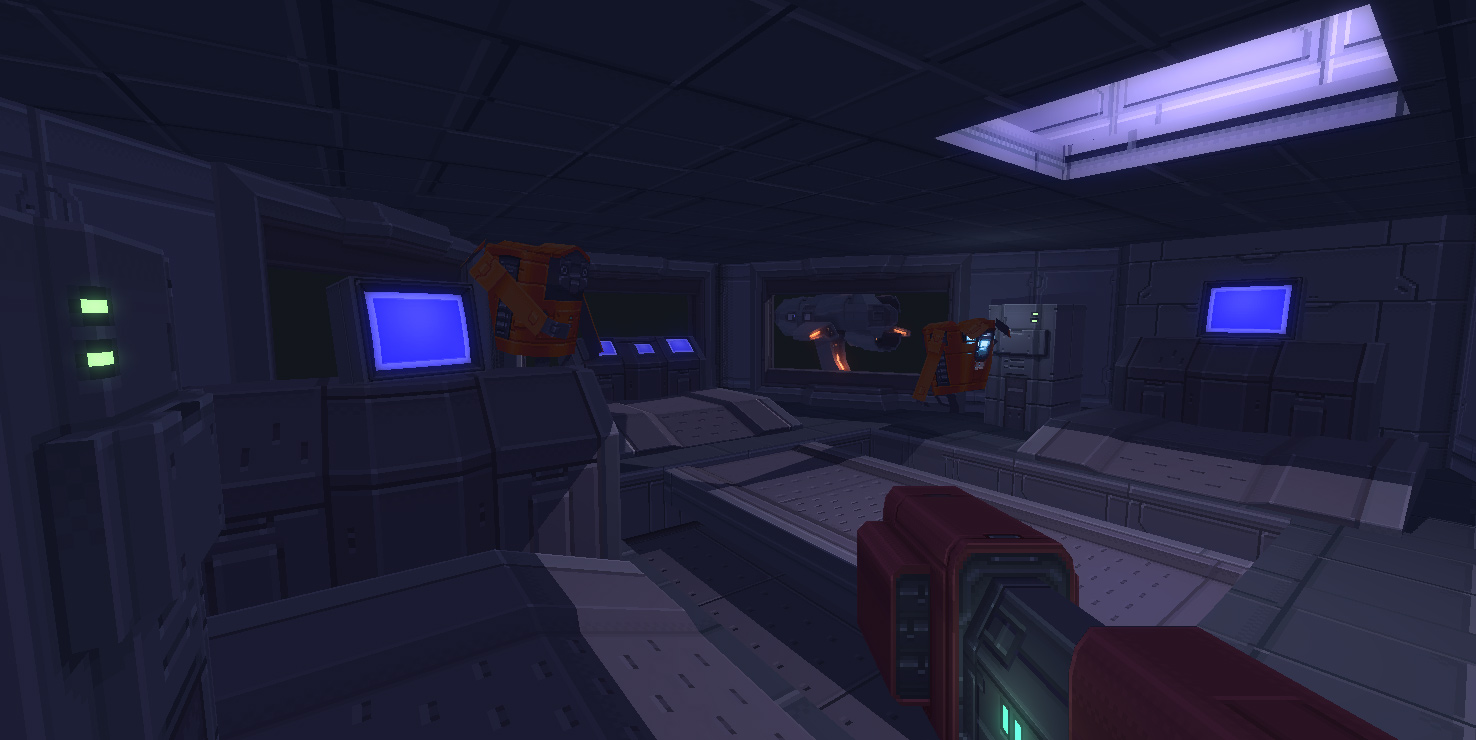

Notch retreated back to his own hobby projects. The millions he made from Minecraft meant that he could afford to. He started creating another game on the scale of Minecraft, which he called 0x10c, an online space-themed game where you can program the computers on your spaceship to complete tasks for you even while you’re not playing the game.

An early prototype of 0x10c.

But now he was a public figure, and he was still the best-known face of Mojang and Minecraft. What this meant is that everything he did was suddenly news, from his tiny little weekend game jam experiments, to the opinions he wrote on his blog, to his marriage and its subsequent collapse a year later. And so 0x10c started getting more attention and more hype than he was able to deal with, despite the fact that it was still in pre-alpha development stages. Because of this pressure and scrutiny, he put the game aside.

And despite his stepping down from Minecraft’s development, he was still the public face of Mojang, and fans still came to him as if he was responsible for Minecraft’s continued progress, with all their gripes and ideas and praise and anger. And that’s a trend that continued to this day.

One last side-story.

Most people who pay attention to the game development scene will have at least heard of Indie Game: The Movie. It was a film created in 2012 that followed three independent game developers making three games, one of them being Phil Fish, creator of Fez.

Phil Fish.

Phil Fish is an interesting case. He has something of a neurotic temperament, and that comes across very heavily in the film—when the film starts, we learn that Fez was already significantly delayed since its introduction and announcement in 2008, in large part due to a falling-out Phil had with a former partner. He spends a good chunk of the film worrying that the former partner was going to block him from showing the game at the Penny Arcade Expo, given that they hadn’t yet signed a final separation deal. This happens only towards the end of the film, and throughout the whole movie he’s portrayed as anxious and difficult to work with.

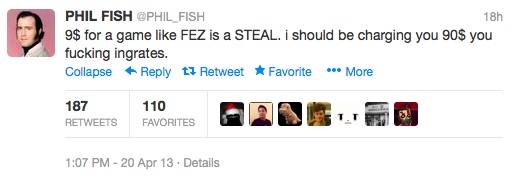

He also takes a very abrasive personality online. He’s frequently insulted or taunted his audience, and his haters, over Twitter, and seems to have difficulty keeping a level head, leading him into countless online arguments.

Last year, Phil got into an argument with Marcus Beer, a video-maker for GameTrailers. Marcus was critical of Phil, complaining about the combination of Phil’s behaviour and his position in the industry. But given that the argument happened through videos at GameTrailers and through Twitter, it was completely public. And that meant that the rest of the internet could, and did, jump into the fray.

The net result of that storm was Phil cancelling the sequel to Fez and announcing he was leaving the games industry. He posted the following on his company’s website:

Fez 2 is cancelled. I am done. I take the money and I run. This is as much as I can stomach. This isn’t the result of any one thing, but the end of a long, bloody campaign. You win.

And later, on Twitter:

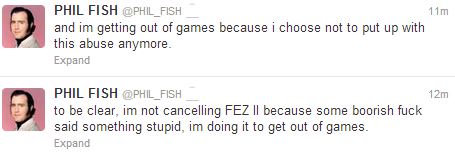

But despite the finality of those statements, that wasn’t the end of his online presence. He still stayed moderately active on social media, up until recently. It was only when he was swept up into the Zoë Quinn scandal that things finally hit rock bottom. In leaping to Zoë’s defence, he once again got himself swept up into a heated internet argument, making himself a target for the same abuse that was directed at Zoë. And he suffered as bad as her if not worse, with the servers of his company, Polytron, being hacked, and everything from his home address, to his social security number, to his personal banking information, to Polytron’s passwords and financial information being distributed around the internet in a huge 1.5 GB file.

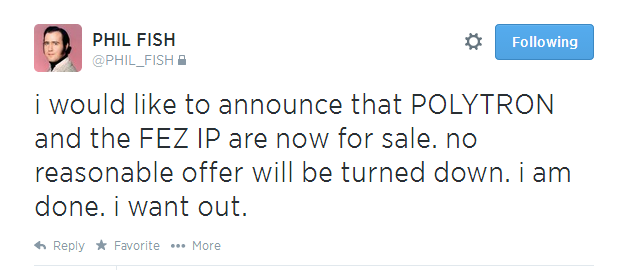

This time, it culminated in him announcing that Polytron and the Fez IP were up for sale.

Despite his efforts to distance himself from Minecraft, Notch was still in the spotlight, and still held responsible for everything that was happening in and around the Minecraft community. And just this past June, Mojang clarified a rule on Minecraft’s end-user license agreement, essentially preventing those who ran online game servers from selling in-game items for money.

At this point, Minecraft servers were a mini-market of their own, with many, many servers charging their users in different ways so they could play. Server administrators had been experimenting with many different ways of covering server costs, from the traditional way of simply charging people to access the server, to other methods, such as allowing free access to the servers but charging for in-game items and perks. The clarification to the EULA took away several options that server administrators had to monetize them, and that made a lot of server administrators, as well as the people who played on those servers, upset.

And despite not being involved in the slightest, Notch again had to bear the brunt of it, writing on his personal blog:

I don’t even know how many emails we’ve gotten from parents, asking for their hundred dollars back their kid spent on an item pack on a server we have no control over. This was never allowed, but we didn’t crack down on it because we’re constantly incredibly swamped in other work.

The whole debate, and the constant negativity swirling around it, wore him down significantly.

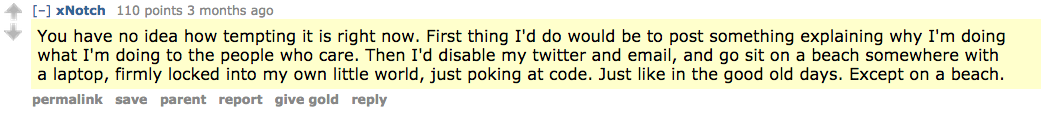

And all of this culminated recently. Rumors starting swirling around of Mojang being bought out by Microsoft, a company that they’d worked with very closely in the past. And then it was confirmed. Microsoft were buying out Mojang for $2.5 billion. And Notch, along with the rest of the founding members, were leaving.

But it wasn’t clear how or why that actually happened until Notch himself wrote about his reasons.

I was at home with a bad cold a couple of weeks ago when the internet exploded with hate against me over some kind of EULA situation that I had nothing to do with. I was confused. I didn’t understand. I tweeted this in frustration. Later on, I watched the This is Phil Fish video on YouTube and started to realize I didn’t have the connection to my fans I thought I had. I’ve become a symbol. I don’t want to be a symbol, responsible for something huge that I don’t understand, that I don’t want to work on, that keeps coming back to me. I’m not an entrepreneur. I’m not a CEO. I’m a nerdy computer programmer who likes to have opinions on Twitter.

This came as a shock to the community. After all, Notch had always seemed positively anti-corporate. This was the man who had cancelled the virtual-reality Oculus Rift version of Minecraft after Oculus was bought by Facebook. The man who had boasted earlier this year about turning down offers in the range of $2 billion. The poster boy for the indie game development dream. But he couldn’t take it. Despite the millions he made, and despite the success, or perhaps because of it, it still wasn’t giving him the life he wanted. Fame wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

As soon as this deal is finalized, I will leave Mojang and go back to doing Ludum Dares and small web experiments. If I ever accidentally make something that seems to gain traction, I’ll probably abandon it immediately.

In the end, Markus Persson is a man. Not a poster boy, not a magical example of the success all indies dream of, but a real human being who has to respond to the real, harsh pressures that befall anyone with a public profile in the games industry. His branding and public image had started to take over his life, the constant pressure and abuse that all people in the spotlight seem to attract was wearing on him, and this was his last, major attempt to reclaim himself.

People are going to complain about this. People are going to see him as a sellout, abandoning the dream life of every independent developer. And they may not understand why he chose this.

But the pressure and negativity is real, and has real consequences. It’s not something everyone can take, and it’s not something anyone should ever have to.

There will be people who complain and criticize him for this decision. But those are the exact same people who drove him to this decision in the first place.

To Markus, I wish you well in whatever you choose to do, and I hope you find a path in life you enjoy.

Forgot password?

Close message

Subscribe to this blog post's comments through...

Subscribe via email

SubscribeComment (1)

Sort by: Date Rating Last Activity

kronopath 21p · 131 weeks ago

This article represents how I felt about him at the time, and still kind of represents how I feel about fame in general. But I don’t look as fondly on him now as I did then.

Post a new comment

Comment as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.

Comments by IntenseDebate

Reply as a Guest, or login:

Connected as (Logout)

Not displayed publicly.